13 Relative Proficiency

13.1 Probability, Odds, and Logits

Most of us are comfortable with the notion of probability, but we find odds to be a little harder to understand. In everyday language, people use probability and odds interchangeably. Technically, they are related, but not at all the same thing.

When the odds of winning are 3 to 1, there will be 3 wins for every loss.

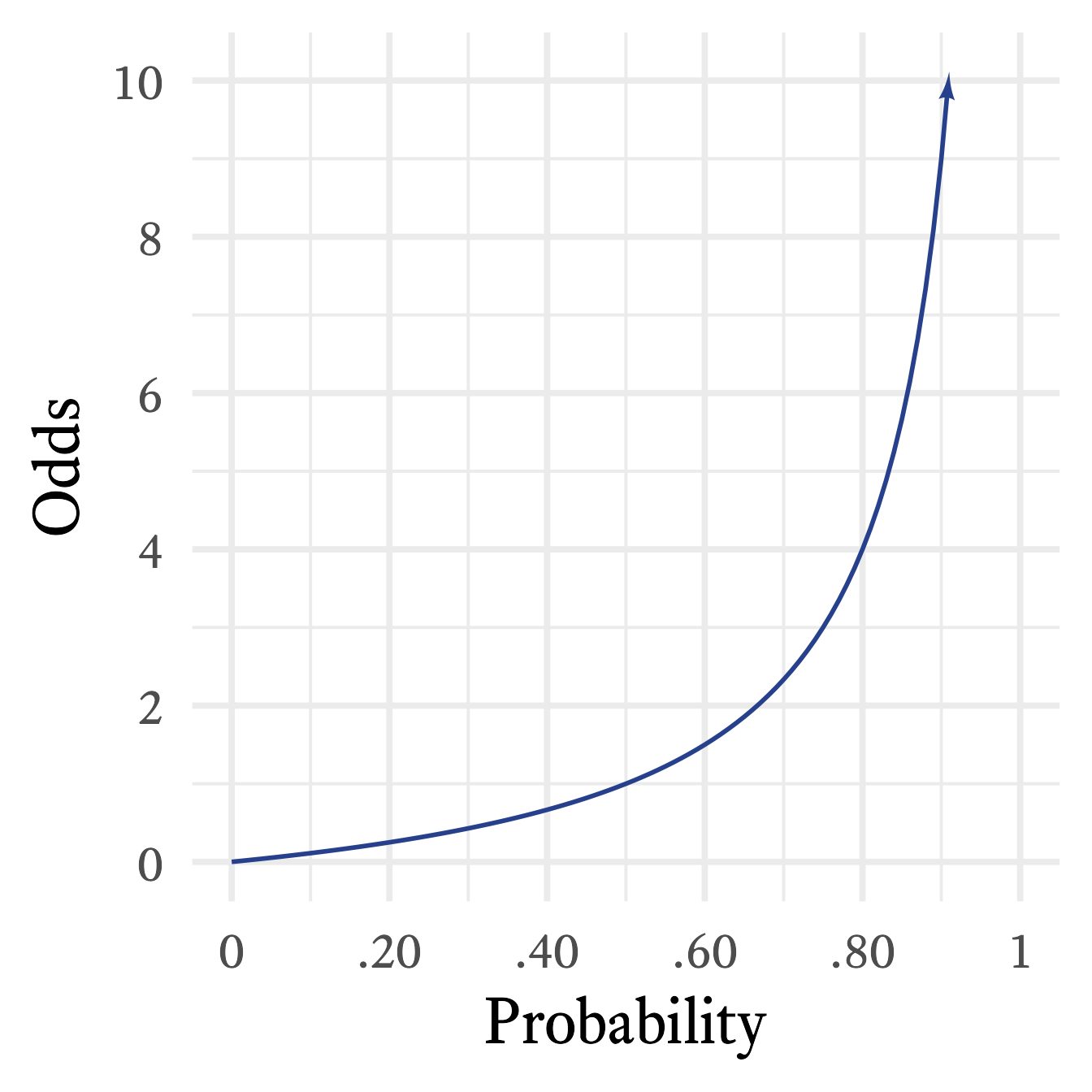

As seen in Figure 13.1, the relationship between probability and odds is not linear. To convert an odds ratio to probability:

p=\frac{odds}{1 + odds}

Thus, 3 to 1 odds is:

odds <- 3 / 1

p <- odds / (1 + odds)

p[1] 0.75Or, 2 to 3 odds is:

odds <- 2 / 3

p <- odds / (1 + odds)

p[1] 0.4To convert probability to odds, one can simply use this formula:

Odds = \frac{p}{1-p}

If the probability of an event is .8, then the odds are:

p <- .8

odds <- p / (1 - p)

odds[1] 4Probabilities bounded by 0 and 1, inclusive. Odds have a minimum of 0 but have no upper bound (See Figure 13.1).

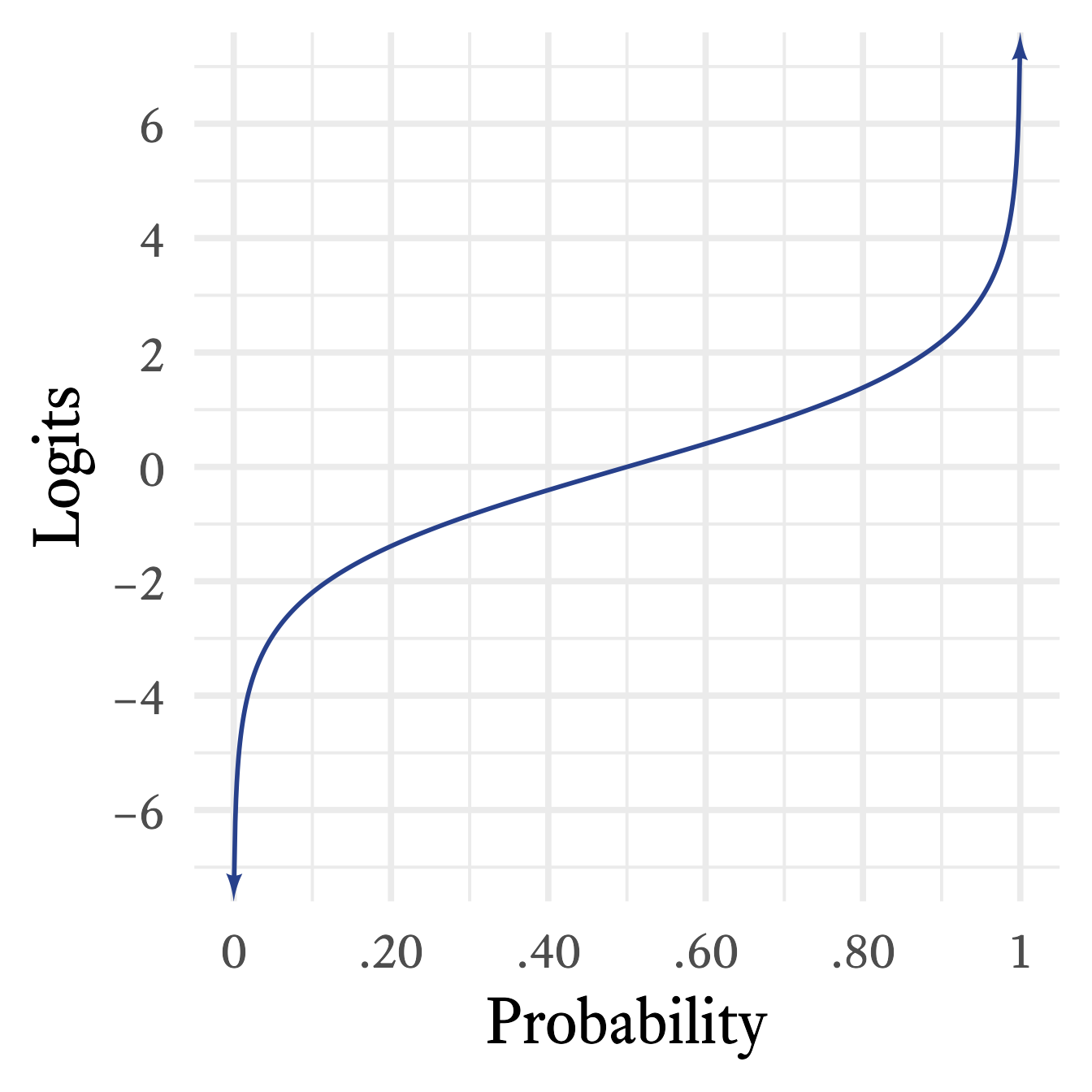

In many statistical applications, we need to convert a probability to a value that has neither upper nor lower bounds. A logit maps probabilities onto real numbers from negative to positive infinity (See Figure 13.2).

A logit is the log-odds of probability.

\text{logit}\left(p\right)=\ln\left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right)

13.2 W Scores

In the same way that we transform z-scores to various kinds of standard scores, we can transform logits to other kinds of scales. The most prominent in psychological assessment is the W-score (AKA Growth Score Values), developed by Woodcock & Dalh (1971). An accessible discussion of its derivation can by found in Benson et al. (2018).

If ability \theta is in logits, then W is calculated like so:

W = \frac{20}{\ln(9)}\theta+500

Although the coefficient \frac{20}{\ln(9)} may seem strange, it has some desirable features. It is equivalent to 20 times the base-9 logarithm of e:

20 \log_9(e) = \frac{20}{\ln(9)} \approx 9.1024

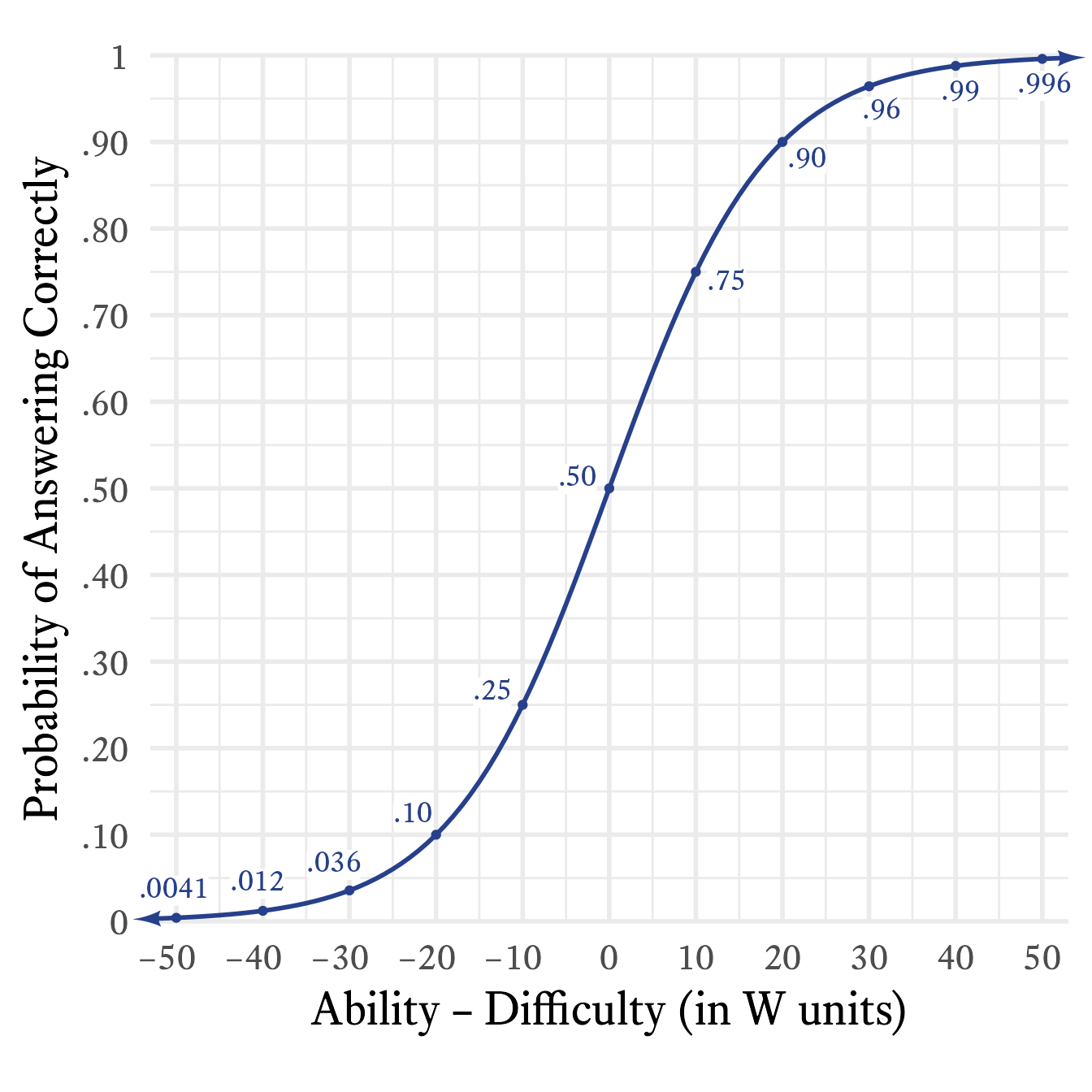

This unusual coefficient yields some nice round probabilities of answering an item correctly when the person’s ability and the item’s difficulty differ by 0, 10, or 20 points (See Figure 13.3).

The probability p of answering an item correctly depends on the difference between the item’s difficulty W_D and the person’s ability W_A. Specifically, the relationship in Figure 13.3 works according to this equation:

p = \left(1 + 9^{\left(W_D-W_A\right)/20}\right)^{-1}

13.3 Relative Proficiency

One of the benefits of item response theory models is that ability is expressed on the same scale as item difficulties. This feature allows us to make predictions about how like a person with a particular ability level will correctly answer an item of a particular difficulty.

The Relative Proficiency Index (RPI) was first used in the Woodcock Reading Mastery Tests (Woodcock, 1973). The RPI answers the following question:

When the average same-age peer with ability \mu_\theta has probability p of answering an item, what is the probability of answering correctly for a person of ability \theta?

The RPI can be calculated like so:

RPI = \left(1+e^{-\left(\theta-\mu_{\theta}+\text{logit}(p)\right)}\right)^{-1} \begin{align*} \theta &= \text{Ability level of person (in logits)}\\ \mu_{\theta} &= \text{Average ability level (in logits) of a reference group}\\ p &= \text{Probability a person with ability } \mu_\theta \text{ will answer correctly}\\ \text{logit}(p) &= \ln\left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right) = p \text{ converted to logits} \end{align*}

The psycheval package can calculate the RPI using the the rpi function. By default, the primary inputs x and mu are assumed to be on the W scale, and the criterion p is .90.

Suppose a person’s ability corresponds to a W-score of 460 and same-age peers have an average W score of 500:

library(psycheval)

rpi(x = 460, mu = 500)0.1This difference of 40 W score points means that when typical same-age peers have a 90% chance of answering an item correctly (a common benchmark for mastery), this person has a 10% chance of answering the item correctly.

If x and mu are logits, then you can specify scale = 1 like so:

rpi(x = 1, mu = 0, scale = 1)0.9607297The RPI works nicely for documenting deficits, but for gifted students, the RPI is quite high, often near 1. In such cases, we can also calculate the probability a person with ability \mu_\theta can answer an item that a person with ability \theta has a probability p_\theta of answering correctly:

RPI_{\text{reversed}} = \left(1+e^{-\left(\mu_\theta-\theta+\text{logit}(p_\theta)\right)}\right)^{-1}

Suppose a person has a W score of 550, which is 50 points higher than typical same-age peers. The standard RPI will give a value close to 1:

rpi(x = 550, mu = 500)0.999543This means that when same-age peers have a 90% chance of answering the item correctly, this person is almost certain to answer it correctly. Unfortunately, this fact does not convey the degree of giftedness in an evocative manner.

To get a better sense of how far advanced this person is compared to the performance of typical same-age peers, we can reverse the RPI like so.

rpi(x = 550, mu = 500, reverse = TRUE)0.03571429This means that when this person has a .9 probability of answering an item correctly, the typical same-age peer has about a .036 probability of answering it. Thus, this person is capable of completing tasks that are quite difficult for typical same-age peers.

The standard RPI refers to a proficiency level of .9, but the rpi function can calculate the relative proficiency index at any criterion level. For example:

rpi(x = 550, mu = 500, criterion = .10)0.9642857This means that when a typical same-age peer has a .10 probability of answering an item correctly, this person will answer it correctly with a .96 probability.

An Excel spreadsheet that calculates this “generalized” RPI can be found here.