rnorm(n = 5, mean = 50, sd = 10)[1] 59.2 52.9 31.8 58.7 68.2Advanced Data Analysis (EDUC 8825)

W. Joel Schneider

February 25, 2025

Once you learn how to simulate data, you will possess a data-science superpower. Generating simulated data allows you to run complicated “What-If” thought experiments, which can help identify implications of models, methods, and procedures that are otherwise difficult to discern. For example, you can ask, if my hypothesized model is correct, what sample size will I need to detect my hypothesized results? Of course, this is what power analysis is for. However, there are many models for which no analytic solution exists, and only simulated data can generate approximate answers to your questions.

Simulated data can help you understand implicit implications of statistical procedures. For example, you might have heard that ANOVA is robust to mild to moderate violations of the normality assumption. How do we know this? Scholars simulated data with normal and non-normal residuals, and found that ANOVA generally came to the correct decision except when the normality assumption was violated to extreme degrees.

Simulated data can help you understand non-obvious implications of complex decisions. For example, Schneider & Roman (2018) used simulated data to show that some well-intentioned diagnostic procedures cause diagnosis of learning disabilities to be less accurate, not more.

Simulated data have a primary limitation: they can only tell you about truths implicit in your model, method, or procedure. To observe genuinely new truths, you must observe genuinely new data.

Sometimes we need to generate simulated data one variable at a time. Let’s generate 5 points from a normal distribution with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10:

Of course, as long as the order of your parameters is what R expects, you can write this code more succinctly like so:

Let’s generate many cases and see if the plot looks normal. We need to put the variable in a tibble because ggplot needs its input to be in a data.frame or tibble.

That looks reasonably normal.

Suppose that we need to generate three variables x, y, and z with means of 50, 75, and 80, and standard deviations of 5, 8 and 9. x and y correlate at 0.6, x and z correlate at 0.7, and y and z correlate at 0.8. The mvtnorm package can help us.

You already know how to set up a vector with the c function. We are going to create a named vector of means. That is, we are going to associate the mean values with their respective variable names. The reason we are doing this is that when we set the mean vector with names, the data generating function will automatically name the columns.

There are, of course, several ways to give vector elements names. Pick one that you like.

We set up the vector of standard deviations in the standard way, though you can apply names to it if you like.

The matrix function takes a vector, and you tell it how many rows and columns the matrix has. If you omit the number of columns, it will figure out how many columns are needed from the number of elements in your vector. In this case, there are 3 elements and 3 rows, so it divides 9 elements by 3 rows and assumes there are 3 columns.

\[\boldsymbol{R}=\left[\begin{array}{r} 1 & .6 & .7 \\ .6 & 1 & .8 \\ .7 & .8 & 1\end{array}\right]\]

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 1.0 0.6 0.7

[2,] 0.6 1.0 0.8

[3,] 0.7 0.8 1.0In a k × k symmetric matrix, the number of redundant elements is

\[\frac{k(k-1)}{2}\]

With a 3 × 3 matrix, it is easy to specify a symmetric matrix because there are only 3 redundant entries. However, imagine how tedious specifying a 20 × 20 matrix with 190 redundant entries would be. With larger matrices, consider specifying just the lower triangle of the matrix, and converting it to a full symmetric matrix using lavaan’s lower2full function. I believe this approach is not only less tedious but also less error-prone.

\[\boldsymbol{R}_{\text{Lower}}=\left[\begin{array}{r} 1 & \\ .6 & 1 \\ .7 & .8 & 1\end{array}\right]\]

The input for lavaan’s lav_matrix_lower2full function is just a vector, but I put line breaks in it to mimic the configuration of the lower triangle of the matrix.

The covariance of x and y (σxy) is the product of the correlation of x and y (rxy) and the standard deviations of x and y.

\[\sigma_{xy}=r_{xy}\sigma_x\sigma_y\]

To convert a correlation matrix R into a covariance matrix Σ using just matrix algebra requires converting the standard deviations into a diagonal matrix D (i.e., standard deviations on the diagonal and zeroes everywhere else).

\[\boldsymbol{D}=\left[\begin{array}{l} \sigma_x&0\\0&\sigma_y \end{array}\right]\]

\[\boldsymbol{\Sigma = DRD}\]

If this conversion process seems like a lot of work, lavaan’s cor2cov function is a quicker alternative:

Now we are ready to generate our multivariate normal data. Let’s generate 1000 cases. The rmvnorm function outputs a matrix, so we usually need to convert it to a tibble.

# A tibble: 1,000 × 3

x y z

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 44.5 68.0 69.7

2 44.8 67.6 62.2

3 51.7 85.7 88.4

4 54.7 76.3 89.3

5 43.8 61.8 71.0

6 43.8 75.2 73.1

7 56.8 79.9 89.8

8 45.1 54.8 53.4

9 49.7 76.1 80.6

10 55.1 97.0 104.

# ℹ 990 more rowsLet’s plot the simulated data

If you want to add marginal density plots, ggExtra’s ggMarginal function looks nice to me.

If you need to simulate data based on a model, the simulateData function from lavaan is quite good. The simsem package takes this approach to the next level, with excellent functions for power analysis.

If you think about things in terms of standardized path coefficients, my own package, simstandard, may be what you are looking for. The advantage of this package is that you do not need to know what the error variances need to be to make the path coefficients standardized.

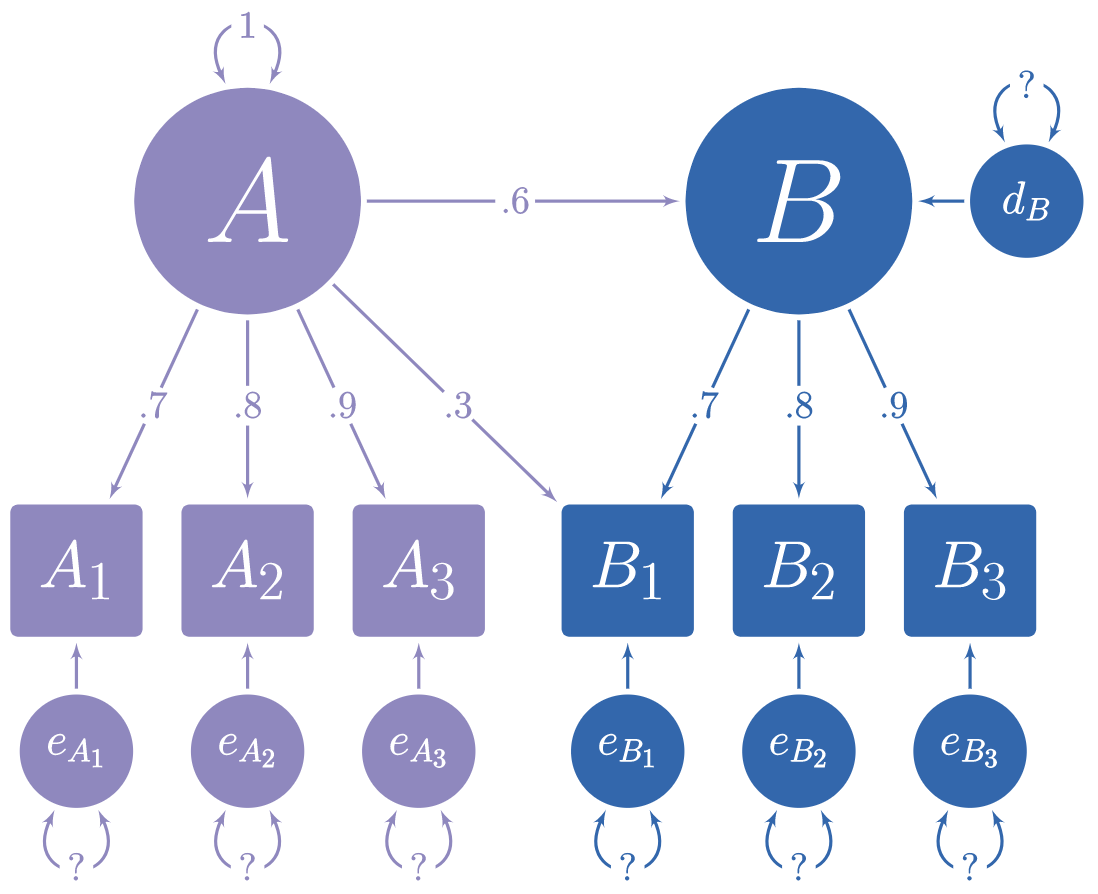

For example, in this model, we know what path coefficients we want, but we do not know what the error variances should be:

Using lavaan syntax, we can specify the model like so:

# A tibble: 6 × 15

A1 A2 A3 B1 B2 B3 A B e_A1 e_A2

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1.00 -0.225 0.110 0.165 -0.477 -0.224 -0.0410 -0.0816 1.03 -0.192

2 0.273 0.773 0.202 -0.359 0.930 0.0657 0.249 -0.576 0.0989 0.574

3 -1.31 -1.24 -0.886 -0.828 -0.957 -0.686 -1.23 -1.74 -0.447 -0.255

4 0.0345 0.467 0.0906 0.409 0.975 -0.548 0.423 -0.289 -0.261 0.129

5 -1.78 0.00422 -0.269 0.0432 -0.582 -0.232 -0.180 -0.0225 -1.65 0.148

6 1.35 -0.165 -1.14 0.116 0.822 0.550 -0.707 0.536 1.85 0.400

# ℹ 5 more variables: e_A3 <dbl>, e_B1 <dbl>, e_B2 <dbl>, e_B3 <dbl>, d_B <dbl>

A =~ 0.7 * A1 + 0.8 * A2 + 0.9 * A3 + 0.3 * B1

B =~ 0.7 * B1 + 0.8 * B2 + 0.9 * B3

B ~ 0.6 * A

# Variances

A1 ~~ 0.51 * A1

A2 ~~ 0.36 * A2

A3 ~~ 0.19 * A3

B1 ~~ 0.168 * B1

B2 ~~ 0.36 * B2

B3 ~~ 0.19 * B3

A ~~ 1 * A

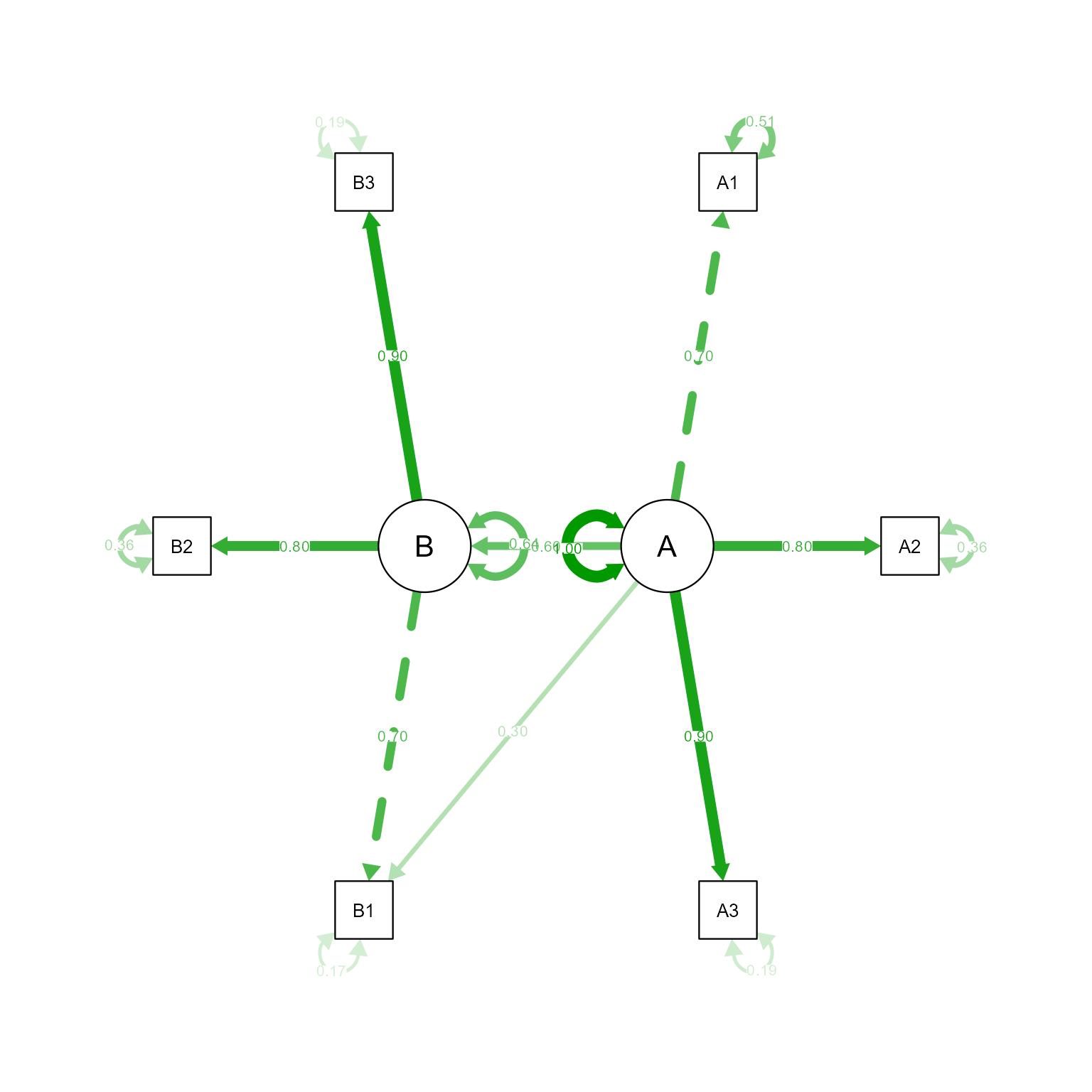

B ~~ 0.64 * BLet’s verify that the simulated data really has the right model. First we take the model and remove all the fixed coefficients.

Now we use lavaan to evaluate the data with the m_free model. The simulated data has the latent variables in the data frame. We need to remove them before this can work:

lavaan 0.6-19 ended normally after 30 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 14

Number of observations 100000

Model Test User Model:

Test statistic 1.857

Degrees of freedom 7

P-value (Chi-square) 0.967

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Standard

Information Expected

Information saturated (h1) model Structured

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

A =~

A1 1.000 0.701 0.700

A2 1.136 0.005 228.623 0.000 0.796 0.798

A3 1.282 0.005 244.965 0.000 0.898 0.899

B1 0.426 0.004 113.363 0.000 0.299 0.299

B =~

B1 1.000 0.698 0.699

B2 1.144 0.005 237.097 0.000 0.798 0.800

B3 1.285 0.005 245.710 0.000 0.897 0.898

Regressions:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

B ~

A 0.600 0.004 140.911 0.000 0.602 0.602

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.A1 0.512 0.003 194.550 0.000 0.512 0.510

.A2 0.362 0.002 166.169 0.000 0.362 0.364

.A3 0.192 0.002 98.333 0.000 0.192 0.192

.B1 0.168 0.001 130.554 0.000 0.168 0.169

.B2 0.358 0.002 177.786 0.000 0.358 0.359

.B3 0.193 0.002 109.202 0.000 0.193 0.193

A 0.491 0.004 120.664 0.000 1.000 1.000

.B 0.311 0.003 123.476 0.000 0.638 0.638

That looks like the model we specified.

In generating multilevel data, we will use the techniques of generating both univariate and multivariate data.

I cannot stress this point strongly enough. Taking the time to write your equations makes subsequent steps so much easier.

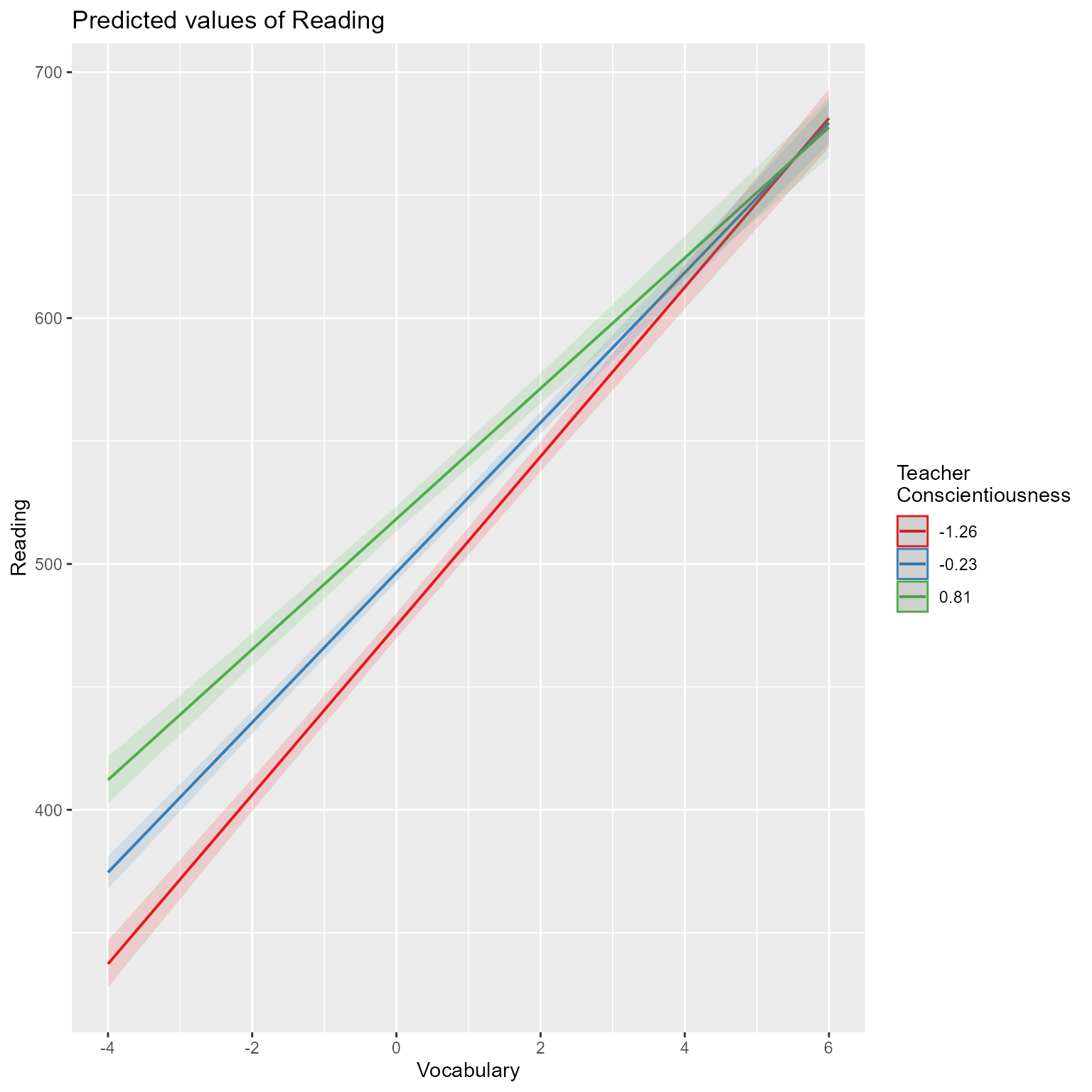

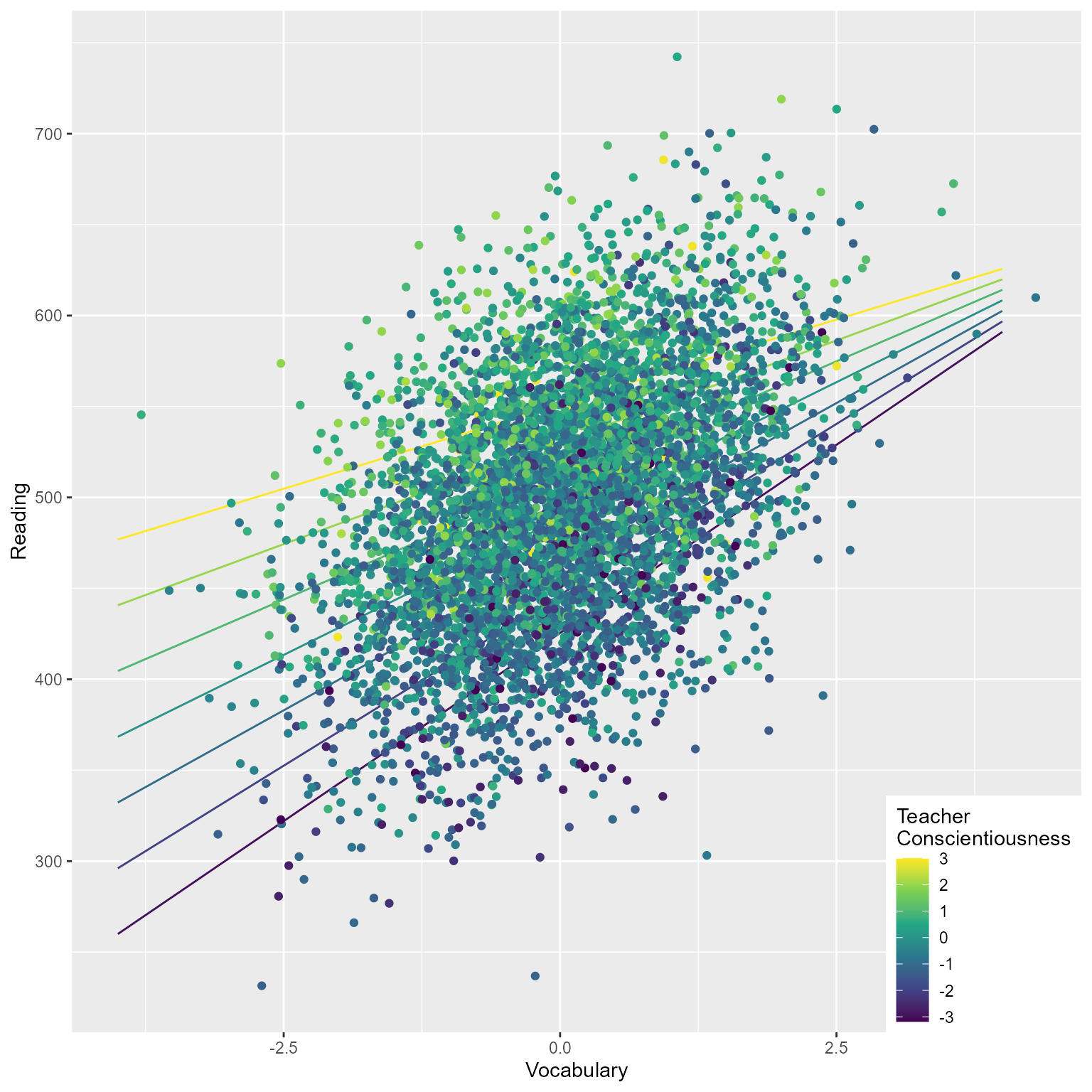

Suppose we want to simulate data in which first-graders’ reading ability is predicted by their vocabulary measured at the beginning of the year and by their first grade teacher’s conscientiousness. Suppose that teacher conscientiousness is expected to help all students learn to read, but it is expected that teacher conscientiousness will be particularly important for students with low vocabulary. That is, the effect of teacher conscientiousness is expected to be stronger for students with low vocabulary compared to students with strong vocabulary. Thus, teacher conscientiousness will have an effect on vocabulary’s random slope.

So, we know that vocabulary is a level-1 variable, and teacher conscientiousness is a level-2 variable. Teacher conscientiousness is expected to have an effect on both the random intercept and vocabulary’s random slope.

Let’s write out the entire equations:

\[ \begin{align*} \textbf{Level 1:}\\[1.5ex] Reading_{ij}&=b_{0j} + b_{1j}V_{ij}+e_{ij}\\ e&\sim\mathcal{N}(0,\tau_1)\\[1.5ex] \text{Where}\\ Reading_{ij}&=\text{Reading score for student } i \text{ in class } j\\ b_{0j} &= \text{Random intercept for class } j\\ b_{1j} &= \text{Random slope for Vocabulary for class } j\\ V_{ij}&=\text{Vocabulary score for student } i \text{ in class } j\\ e_{ij}&=\text{Level-1 error for student } i \text{ in class } j\\ \tau_1 &= \text{Level-1 Error Variance}\\[2ex] \textbf{Level 2:}\\[1.5ex] b_{0j}&=b_{00} + b_{01}C_{j}+e_{0j}\\ b_{1j}&=b_{10} + b_{11}C_{j}+e_{1j}\\ \begin{bmatrix}e_{0j}\\e_{1j}\end{bmatrix}&\sim\mathcal{N}\left(\begin{bmatrix}0\\ 0 \end{bmatrix}\begin{matrix} \\ ,\end{matrix}\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{00}&\\ \tau_{10}&\tau_{11}\end{bmatrix}\right)\\[1.5ex] \text{Where}\\ b_{0j} &= \text{Random intercept for class } j\\ b_{00} &= \text{The expected intercept when } C_j \text{ is 0}\\ b_{01} &= \text{The effect of } C_j \text{ on the random intercept}\\ C_j &= \text{Teacher conscientiousness in class } j\\ e_{0j} &= \text{The random intercept's error for class } j \\ b_{1j} &= \text{Random slope for Vocabulary for class } j\\ b_{10} &= \text{The expected Vocabulary slope when } C_j \text{ is 0}\\ b_{11} &= \text{The effect of } C_j \text{ on the Vocabulary slope}\\ e_{1j} &= \text{The Vocabulary slope's error for class } j \\ \tau_{00} &= \text{The variance of } e_{0j}\\ \tau_{11} &= \text{The variance of } e_{1j}\\ \tau_{10} &= \text{The covariance of } e_{0j} \text{ and } e_{1j} \end{align*} \]

Combining the level-1 and level-2 formulas:

\[Reading_{ij}=\underbrace{b_{00} + b_{01}C_{j}+e_{0j}}_{b_{0j}} + (\underbrace{b_{10} + b_{11}C_{j}+e_{1j}}_{b_{1j}})V_{ij}+e_{ij}\]

By multiplying everything out, we can see exactly how everything needs to be calculated.

\[Reading_{ij}=b_{00} + b_{01}C_{j}+e_{0j} + b_{10}V_{ij} + b_{11}C_{j}V_{ij}+e_{1j}V_{ij}+e_{ij}\]

Now we are ready!

In this case, we have four coefficients, and it is straightforward to specify them all.

Which values should you choose? That is determined by theory. With complex models like this one, sometimes there is a bit of trial-and-error to get parameter values that produce data that are consistent with the theory you have in mind.

You need to remember whether you set this number up as a variance or as a standard deviation. I am setting it up as a variance.

\[\boldsymbol{\tau}_2=\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{00}&\\ \tau_{10}&\tau_{11}\end{bmatrix}\]

I have written out the \(\boldsymbol{\tau}_2\) matrix showing only the lower triangle of the matrix because the upper triangle is redundant. I think it is safer to write the lower triangle rather than specifying the full matrix with its duplicate covariancs.

:::

We can create the \(\boldsymbol{\tau}_2\) matrix like so:

# Variance of intercepts

tau_00 <- 25 ^ 2

# Variance of Vocabulary slope

tau_11 <- 0.4 ^ 2

# Correlation of intercepts and Vocabulary slopes

r_10 <- -.4

# Covariance of intercepts and slopes

tau_10 <- sqrt(tau_00 * tau_11) * r_10

# tau lower triangle in vector form

tau_lower_triangle <- c(tau_00,

tau_10, tau_11)

# Convert lower triangle to a full symmetric matrix

tau_2 <- lavaan::lav_matrix_lower2full(tau_lower_triangle)It is generally best to start with a small number so that you simulations will run quickly. You can increase the number of clusters later. Let’s start with 100 groups. We will use the variable k to refer to the number of clusters.

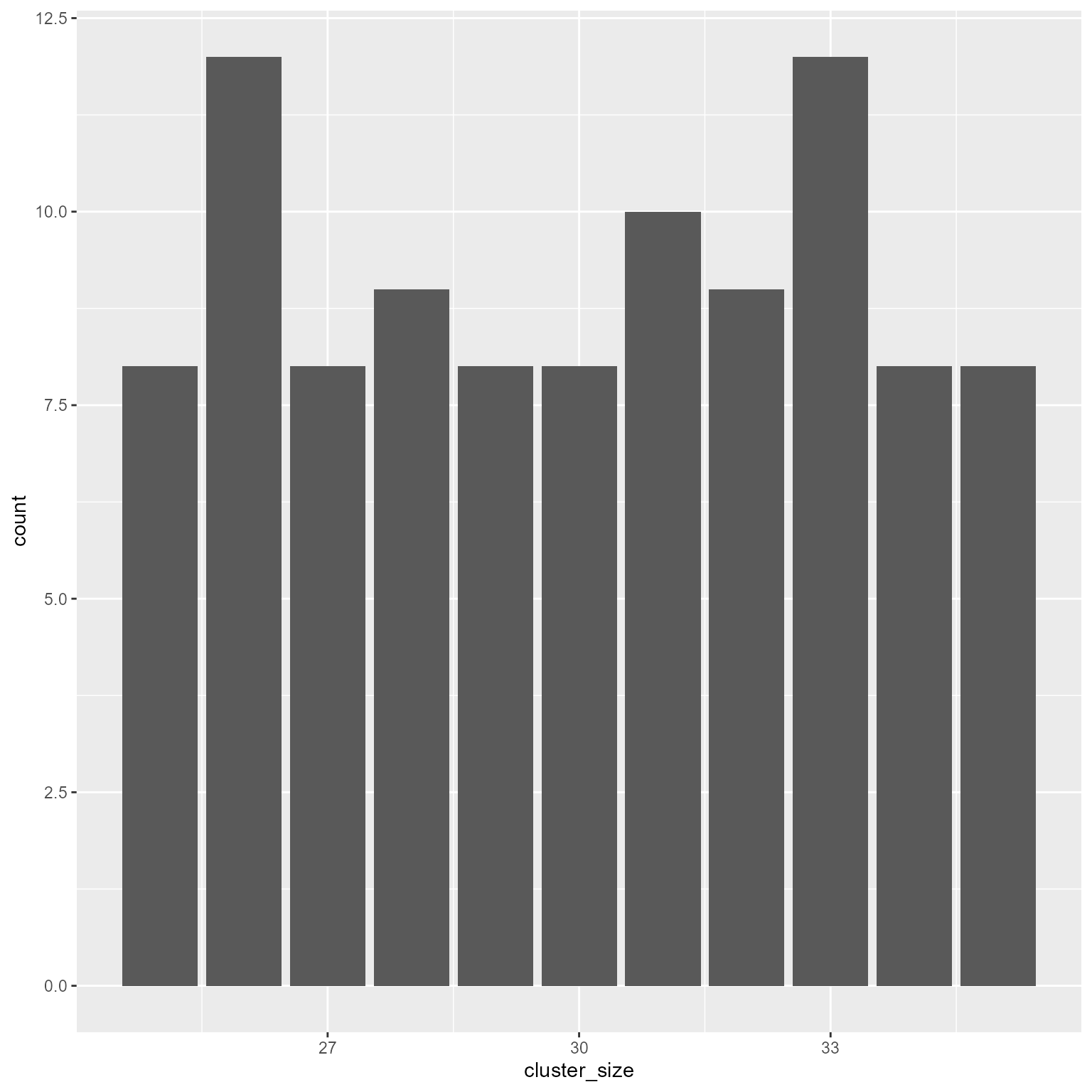

Option 1 Every cluster has the same size.

Option 2 Cluster size is determined by a random variable.

Which random variable? It is up to you. Some common choices include the normal distribution, Poisson distribution, or the uniform distribution.

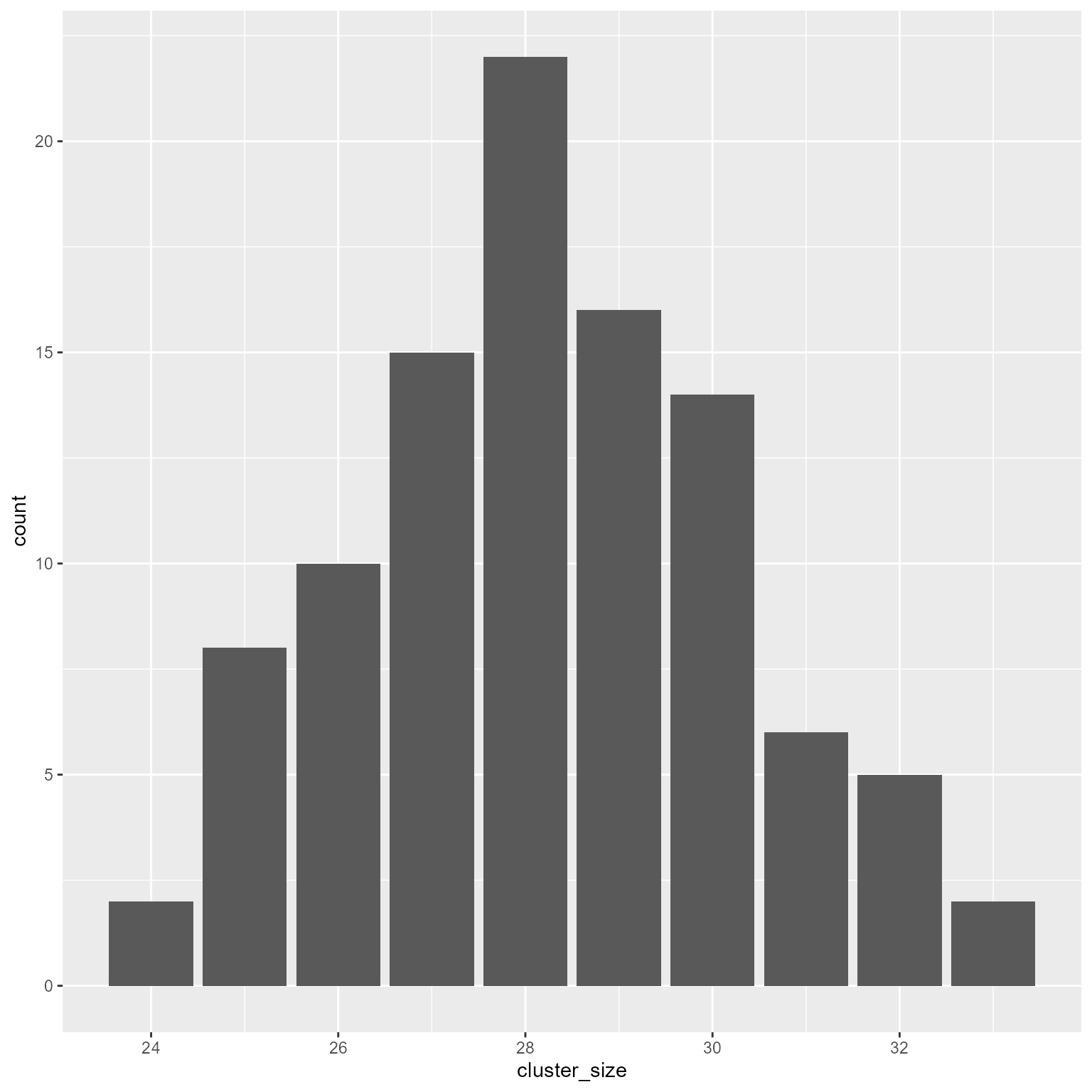

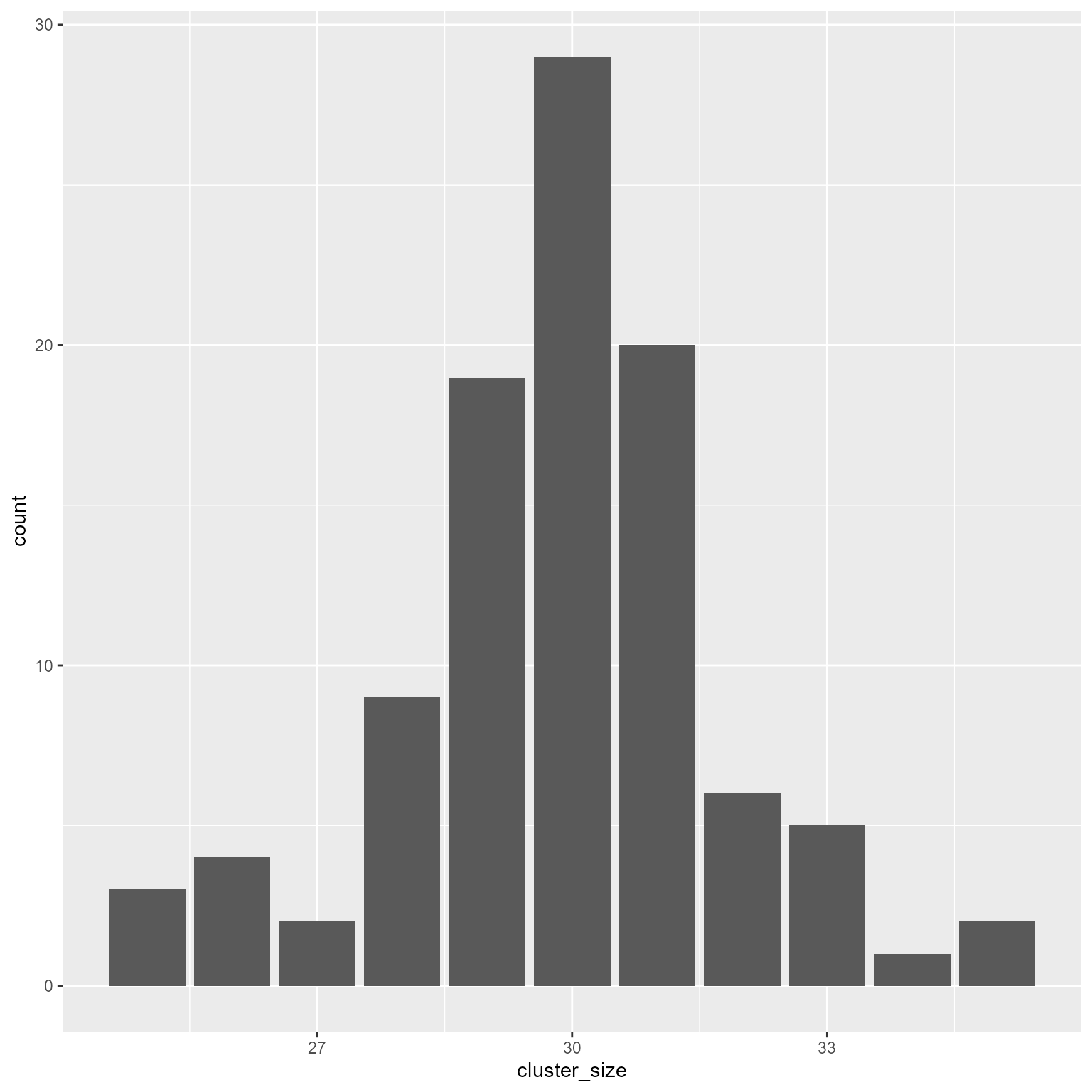

pmax function. It replaces any vector element less than the lower limit with the lower limit. For example:Here we generate a normal variate with a mean of 28 and a standard deviation of 2.

The binomial distribution is also a good choice for generating non-negative numbers.

sample function to have cluster sizes uniformly distributed between 2 values.

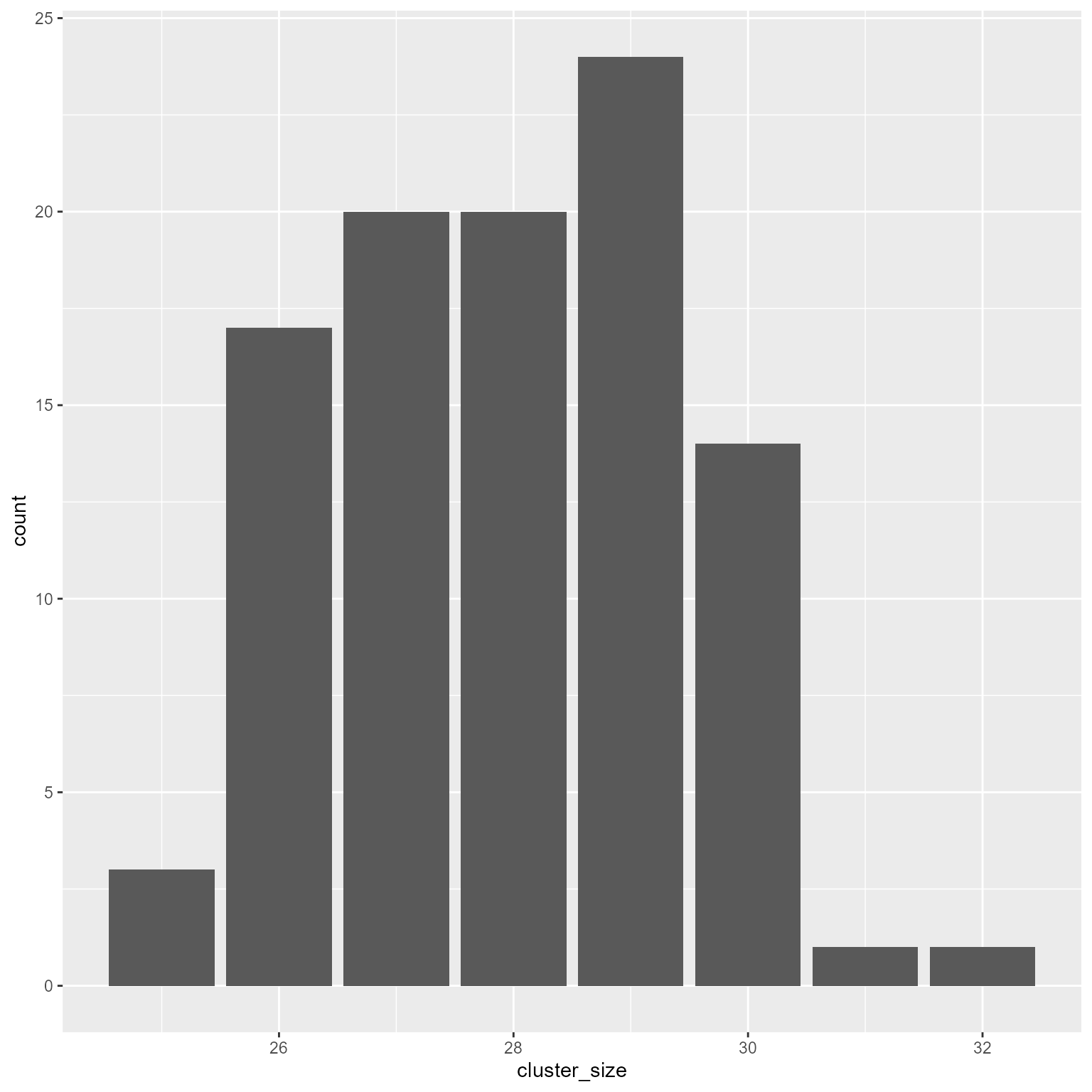

Option 3 Make your own distribution function.

prob argument in the sample function.# A tribble is a "transposed tibble" that is easy to view.

# I pasted it directly from Excel using the datapasta RStudio addin

d_probs <- tibble::tribble(

~sample_space, ~probability,

25L, 0.01,

26L, 0.02,

27L, 0.04,

28L, 0.10,

29L, 0.20,

30L, 0.30,

31L, 0.20,

32L, 0.08,

33L, 0.03,

34L, 0.01,

35L, 0.01)

cluster_size = sample(

x = d_probs$sample_space,

prob = d_probs$probability,

size = k,

replace = TRUE)

d2 <- tibble(cluster_id, cluster_size)

ggplot(d2, aes(cluster_size)) +

geom_bar()

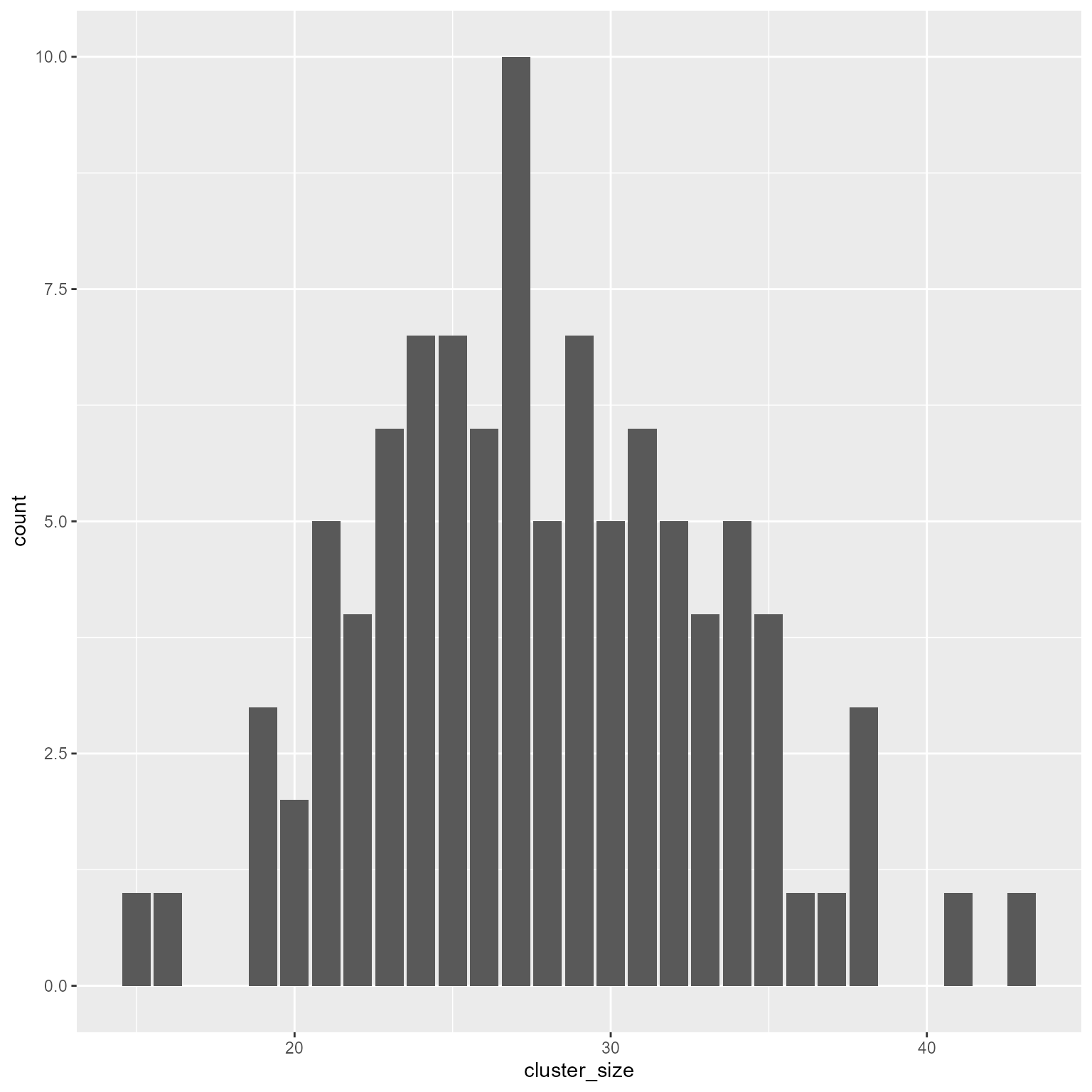

sample function to generate new data with the same proportions as the real data.# Pretend that x is a vector with real data on class sizes.

# Also pretend that we do not know how it was made.

# All we know is the data in x.

d_x <- tibble(x = round((rpois(10000, 28) - 28) * 0.3, 0) + 28) %>%

group_by(x) %>%

summarise(probability = n() / nrow(.))

# Generate new data based on same proportions

cluster_size <- sample(x = d_x$x,

size = k,

replace = TRUE,

prob = d_x$probability) %>%

as.integer()

d2 <- tibble(cluster_id, cluster_size)

ggplot(d2, aes(cluster_size)) +

geom_bar()

We will use the τ matrix to simulate u0j and u1j.

Recall that

\[\begin{bmatrix}e_{0j}\\e_{1j}\end{bmatrix}\sim\mathcal{N}\left(\begin{bmatrix}0\\ 0 \end{bmatrix}\begin{matrix} \\ ,\end{matrix}\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{00}&\\ \tau_{10}&\tau_{11}\end{bmatrix}\right)\]

Create level-2 error terms.

How you simulate the level-2 predictors depends on theory. Personality variables like conscientiousness usually have a normal distribution. I am going to make things simple by creating a standard normal variate (mean = 0, sd = 1).

The bind_cols function binds the columns of two data.frames (or tibbles).

# A tibble: 100 × 7

cluster_id cluster_size C_j e_0j e_1j b_0j b_1j

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 33 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

2 2 28 0.405 32.7 -0.212 541. 28.2

3 3 19 0.944 -25.7 -0.311 493. 25.9

4 4 24 0.418 -9.27 -0.0941 499. 28.2

5 5 30 -1.20 28.2 -0.859 504. 33.9

6 6 36 -0.423 -48.6 -0.213 443. 31.5

7 7 29 1.10 -10.0 0.0453 512. 25.7

8 8 41 0.989 -0.120 0.230 520. 26.3

9 9 37 -0.618 22.9 0.0493 511. 32.5

10 10 29 0.586 -10.3 0.0828 501. 27.7

# ℹ 90 more rowsThe uncount function makes this step easy. It duplicates a row the number of times specified in the weights variable—the cluster size in this case.

# A tibble: 2,787 × 6

cluster_id C_j e_0j e_1j b_0j b_1j

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

2 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

3 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

4 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

5 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

6 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

7 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

8 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

9 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

10 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5

# ℹ 2,777 more rowsThe rnorm function needs to know how many rows there are. Because the number of rows was generated randomly, we do not usually know how many rows there will be. Fortunately, we can use the n function, which tells us how many rows are in a data frame.

# A tibble: 2,787 × 8

cluster_id C_j e_0j e_1j b_0j b_1j V_ij e

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -1.65 1.34

2 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -0.0635 -5.36

3 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -1.79 -0.924

4 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -0.326 0.730

5 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 0.180 1.77

6 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 1.40 -2.98

7 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 0.546 -6.83

8 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -0.0393 1.59

9 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -0.0401 -0.279

10 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 1.57 -7.86

# ℹ 2,777 more rowsIf we have written out the level-1 equation, this step is easy.

\[Reading_{ij}=b_{0j} + b_{1j}V_{ij}+e_{ij}\]

# A tibble: 2,787 × 9

cluster_id C_j e_0j e_1j b_0j b_1j V_ij e Reading

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -1.65 1.34 437.

2 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -0.0635 -5.36 482.

3 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -1.79 -0.924 430.

4 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -0.326 0.730 480.

5 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 0.180 1.77 497.

6 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 1.40 -2.98 532.

7 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 0.546 -6.83 500.

8 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -0.0393 1.59 490.

9 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 -0.0401 -0.279 488.

10 1 -0.614 1.67 0.0213 489. 32.5 1.57 -7.86 532.

# ℹ 2,777 more rowsIn the context of this tutorial, it might seem like the number of steps was really, really long. It is not actually all that bad. Let’s see what things look like put together:

set.seed(9)

pacman::p_load(tidyverse, mvtnorm, lavaan, lme4)

# Number of clusters

k <- 200

# Fixed coefficients

# Fixed intercept

b_00 <- 500

# Teacher conscientiousness effect on intercept

b_01 <- 20

# Fixed slope for Vocabulary

b_10 <- 30

# Teacher conscientiousness effect on Vocabulary's slope

b_11 <- -4

# Level-1 error standard deviation

tau_1 <- 50 ^ 2

# Random variances

# Variance of intercepts

tau_00 <- 25 ^ 2

# Variance of Vocabulary slope

tau_11 <- 0.4 ^ 2

# Correlation of intercepts and Vocabulary slopes

r_10 <- -.4

# Covariance of intercepts and Vocabulary slopes

tau_10 <- sqrt(tau_00 * tau_11) * r_10

# Level-2 covariance matrix

tau_2 <- lav_matrix_lower2full(c(tau_00,

tau_10, tau_11))

# Level-2 error terms

e2 <- rmvnorm(k,

mean = c(e_0j = 0, e_1j = 0),

sigma = tau_2) %>%

as_tibble()

d <- tibble(cluster_id = factor(1:k),

cluster_size = rpois(k, 28) %>% pmax(1),

C_j = rnorm(k)) %>%

bind_cols(e2) %>%

mutate(b_0j = b_00 + b_01 * C_j + e_0j,

b_1j = b_10 + b_11 * C_j + e_1j) %>%

uncount(cluster_size) %>%

mutate(V_ij = rnorm(n()),

e = rnorm(n(), sd = sqrt(tau_1)),

Reading = b_0j + b_1j * V_ij + e,

cluster_id = fct_reorder(cluster_id, C_j))Let’s see what our simulated data look like

Linear mixed model fit by REML ['lmerMod']

Formula: Reading ~ 1 + C_j * V_ij + (1 + V_ij | cluster_id)

Data: d

REML criterion at convergence: 59809

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-4.767 -0.660 0.005 0.645 3.396

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

cluster_id (Intercept) 574.520 23.969

V_ij 0.495 0.704 -1.00

Residual 2511.846 50.118

Number of obs: 5571, groups: cluster_id, 200

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error t value

(Intercept) 501.334 1.874 267.53

C_j 20.967 1.794 11.69

V_ij 29.615 0.702 42.20

C_j:V_ij -3.797 0.662 -5.74

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr) C_j V_ij

C_j 0.222

V_ij -0.072 -0.010

C_j:V_ij -0.010 -0.079 0.214

optimizer (nloptwrap) convergence code: 0 (OK)

boundary (singular) fit: see help('isSingular')We see that our fixed effect and random variance estimates are reasonably close to our population parameters.

| Effect | Parameter | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| \(b_{00}\) | 500 | 501.33 |

| \(b_{01}\) | 20 | 20.97 |

| \(b_{10}\) | 30 | 29.61 |

| \(b_{11}\) | -4 | −3.80 |

| \(\tau_{00}\) | 625 | 574.52 |

| \(\tau_{10}\) | -4 | −16.87 |

| \(\tau_{11}\) | 0.16 | 0.50 |

Not bad. The variance components look a bit off. I am not showing the results here, but when I increased the level 1 and level 2 sample sizes to much larger values, the tau matrix approximated the correct values. The model took a looooooong time to run. However, it was worth the wait because I now have confidence that the data are being generated correctly.

Alternately, make the plot yourself

d_augmented <- broom.mixed::augment(fit)

# Make fitted values for conditional slopes

d_conditional_slope_v <- broom.mixed::augment(

fit,

newdata = crossing(C_j = -3:3,

V_ij = c(-4, 4),

cluster_id = factor(1))) %>%

rename(Reading = .fitted)

ggplot(d_augmented, aes(V_ij, Reading)) +

geom_line(data = d_conditional_slope_v, aes(group = C_j, color = C_j)) +

geom_point(aes(color = C_j)) +

scale_color_viridis_c() +

theme(legend.position = c(1, 0),

legend.justification = c(1, 0)) +

labs(x = "Vocabulary", color = "Teacher\nConscientiousness")

There are many R packages for simulating multilevel data. I recommend checking out simr and simstudy.